Geologic Time

This geologic time chart contains a lot of information, but tells a wonderful story. The chart starts at the bottom with the formation of the earth, describes each geologic period, indicates what was living when, and the six different extinctions that have occurred over the history of our planet, starting 540 million years ago (mya). Prior to that, the continents were more like one large land mass, constantly moving, breaking apart, joining up, and so on … a very turbulent time from the time the earth formed 4.5 billion years ago. You can see from the chart that little critters (greater than single cell) did not emerge until the beginning of the Cambrian era. During this period, North America actually sat on the equator bordered by 3 oceans. Thus, a lot of what is now the US was underwater and experiencing a lot of volcanic activity and rock upheavals. There have been six different extension events that have been identified, occurring during the formation of our modern day planet. The most well-known extinction (to humans) is when the dinosaurs died off. This occurred 66 million years ago. At this time 76% of creatures went extent. At the end of all the pictures is a more in-depth description of what and where we saw these formations, fossils, and bear droppings that I’ve pictured. A lot of the narrative has been edited out.Current time (NOW) is referred to as the Anthropocene. You’ll note that there is a “?” about how much extinction man has caused.Given all its mountains and diversity of the terrain, Wyoming is a great state to see geologic history … from the Cambrian era onward to modern times.

We flew into Billings, Montana and stayed at the Yellowstone Bighorn Research Center outside of Red Lodge, MT. The next day we drove to Cody, WY to check out Elk Basin, Polecat Bench, and Clarks Fork Canyon. The following day was exploration in the morning and visiting the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. After two nights in Cody, we headed out to Yellowstone but decided to turn back and look for fossils (outside of the park) and then back to Red Lodge along a northern route, Beartooth Pass, cutting through a bit of Montana. This is where we had a panoramic view of all the mountains around us at 11,000 feet. After a night in Red Lodge, it was time to say goodbye and fly home.

Along with the pictures above, I will describe a few of the things we saw along the way, courtesy of Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in DC.

It is an amazing amount of information to process. So, I will give a snippet of his trip description here.

The first we left the Bighorn Research Center, just outside Red Lodge, and headed for some interesting formations.

Polecat Bench

We then drove out of a basin up on to a very flat plateau known as Polecat Bench. The flat surface was formed when the ancient Shoshoni River flowed across the surface and planed the existing geology flat. This kind of structure is known as a pediment (as opposed to a terrace which is formed by the build of river gravels or a mesa which is formed by a resistant, flat-lying rock layer).

We drove along Polecat Bench to its southern margin and then down to its southernmost point for our lunch stop. Some of us saw a young golden eagle lift off from his perch at the edge of the bench. At the lunch stop, we all looked at the gravel that capped the bench and saw that most of it was composed of round (tumbled by a river), dark gray pebbles of volcanic rock. They came from the ancient Shoshone River. At some point in the last few hundred thousand years, the Shoshone had flowed out of the its canyon near Cody, across what is now Polecat Bench and out of the basin to the north, passed to the west of the Pryor Mountains where it eventually flowed into the Yellowstone River which flowed into the Missouri River which flowed into Mississippi River which flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. Well, you get the point. As we sat at the edge of the bench looking down to the irrigated fields near the town of Powell, we could see that the modern course of the Shoshone River was hundreds of feet below us.

On the southern flanks of Polecat Bench we could see the red and tans striped layers (Badlands) of the Eocene (56-55 million-year-old Formation). The layers at the end of the bench were deposited at a time of intense global warming known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (or PETM). During this time the small mammals like the dog-sized early horses were made even smaller by thermally driven dwarfing (imagine a cat-sized horse!).

Finally, we also had our first really good view of Heart Mountain to the south. This mountain is one of the greatest geological conundrums on the planet. The top of the mountain is Mississippian Madison Limestone and it is sitting directly on top of flat-lying Willwood Formation. This arrangement seems to violate the rule of superposition which states that the younger rocks are on top of older rocks. A puzzle since it was first seen, Heart Mountain appears to have slid into place around 50 million years ago (this is after the Beartooth Mountains were uplifted and it is roughly the same time as the volcanic eruptions that formed the Absaroka Mountains that occur to the east of Yellowstone).

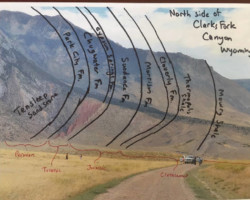

Clarks Fork Canyon

We then drove down the flank of Polecat Bench to the town of Powell. Then, we drove west, through the Sand Coulee badlands, across the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone, through the tiny town of Clark, Wyoming and into the mouth of the majestic Clarks Fork Canyon. Early efforts to build a highway to Yellowstone National Park through this canyon failed but they did result in a splendid road to nowhere that enters the canyon and then stops dead in its tracks.

From this vantage point, we could see some truly jaw-dropping geology. The mouth of the canyon shows the uplifted Precambrian metamorphic rocks draped with the folded layers of Cambrian, Ordovician, Devonian, Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian layers, further out from the canyon mouth, the Triassic (these are the brilliant red beds of the Chugwater Formation that caught everyone’s attention), Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Paleocene layers are exposed as planed off outcrops of vertically tilted beds. To top it off, the old mouth of the canyon is corked by, not one but, two terminal glacial moraines, evidence of the huge ice sheet that covered Yellowstone during the Ice Age. This one canyon tells much more of Earth’s story than does the Grand Canyon and I know of no place better in the whole world to see so much time in one place.

After that, we drove into Cody, WY.

Cody

Buffalo Bill Dam at Rattlesnake Mountain

Day 2 we drove up to Rattlesnake Mountain. This mountain, like Elk Basin, is a dome-like geologic structure along the western margin of the Bighorn Basin. Unlike Elk Basin it is a topographic dome as well as a geologic one. The Shoshone River has cut right through the mountain and the dam is located at the zone of the deepest cut. When rivers cut mountains it means that they were there before the mountains and that is certainly the case with Rattlesnake Mountain.

Looking across the river, we had an excellent view of the “Great Unconformity.” This is where Precambrian metamorphic rocks that are more than 2.7 billion years old are overlain by the Cambrian (515 million-year-old) Flathead Sandstone. The time that is missing at this contact is a whopping 2.2 billion years (remember that the Earth is 4.567 billion years old so half of our planet’s history happened in the time represented by the contact of these two rock units).

We then drove up to Elk Creek for a little hike but were dissuaded from our plan by a bunch of nervous packers who had encountered a sow grizzly with two cubs just a few hundred yards up the trail. There was a unanimous consensus to hop in the trucks and head for plan B.

Mummy Cave

A few miles further up the road, we stopped to look at Mummy Cave, a rock shelter that had been excavated in the 1970s and had yielded a human mummy along with evidence of more or less continuous habitation from about 9800 years ago to the recent past. While we looked at the cave, a couple of yellow-bellied marmots whistled at us and we notice some very fresh piles of bear scat. With more than 700 grizzlies now roaming the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem, it pays to travel in groups, carry bear spray, and make a lot of noise. That we did.

Buffalo Bill Center for the West

We returned to Cody for lunch at the Buffalo Bill Center followed by tours of the museums: the Draper Museum of Natural History, the western art in the Whitney Museum (a lot of beautiful works, including many by Remington, an artist who has done many sculptures and paintings of the West). We also were given a behind the scenes tour in the vault to see a bunch of Buffalo Bill memorabilia (most of us got a chance to wear Bill’s hat).

Cody to Red Lodge

Heart Mountain

We headed north out of Cody, crossed the Shoshone River and passed the west flank of Heart Mountain. In addition to being a geologic puzzle, Heart Mountain is also the site of one of the Japanese internment camps from World War II.

Dead Indian Hill

We turned west and drove up the long slope of Dead Indian Hill. We were now headed west on the trail where Chief Joseph led the Nez Pearce Indians east as they fled the U. S. Army in August of 1877. The entire population of the tribe walked from northeastern Washington to northern Montana in an attempt to seek shelter with the Crow Indian Nation.

At the top of the hill, we drove up a gravel road and gained a splendid view of the Absaroka Mountains and Sunlight Basin to the southwest and the Beartooth Plateau and Beartooth Butte to the northwest. As we drove down the hill we stopped to look for trilobites in the Cambrian shale but only found the in-filled burrows of long-dead marine worms (500 million years old).

Cooke City

We followed the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone into Cooke City, Montana. We stopped briefly for drinks and were ensnared by a lovely little pop-up rock shop that managed to collect a lot of our loose change. I’m a big fan of rock shops and this was a good one that had a whole bunch of interesting stuff at very reasonable prices.

Passing Silver Gate, we entered the northeast gate of Yellowstone, but we all decided that we did not need to go into the park. This used to be a great place for a hike but the number of bears and wolves in the valley has now made it a little trickier to look at petrified trees. After a quick lunch, we turned around and retraced our path back to Cooke City and up onto the Beartooth Plateau.

Beartooth Butte

We stopped at the scenic Beartooth Butte.

While we were admiring the rocks, one of our tires decided to leak and a crack team assembled on the spot to get it changed. Other members of the team took the opportunity for a quick dip in Beartooth Lake. Brrr!

Top of the World

At the Top of the World, we broke above the timber line and out into a lovely alpine meadow that was being abused by a large variety of heavy equipment. We pulled over and walked across the alpine tundra to some uninspiring outcrops of Cambrian Wolsey Shale which turned out to contain quite a few trilobite heads and tails (I don’t think we got any whole ones). These fossils are well over 500 million years in age and some of the oldest marine fossils in the world. Woohoo for fossils!!!!!

The Beartooth Highway

We then climbed to the top of the plateau. At over 11,000 feet, this was truly alpine terrain and we walked across crack boulder fields known as “felsenmeer” for a few hundred photographs. From there it was all downhill via an endless series of switchbacks to the glacial valley of Rock Creek and a short drive into Red Lodge for our final night at the Pollard Hotel.